To Convert or Refit ... Or Not

THE HARD FACT IS THERE AREN'T ANY MIRACULOUS SAVINGS TO BE HAD IN MAJOR CONVERSIONS, REFITS, AND REFURBS

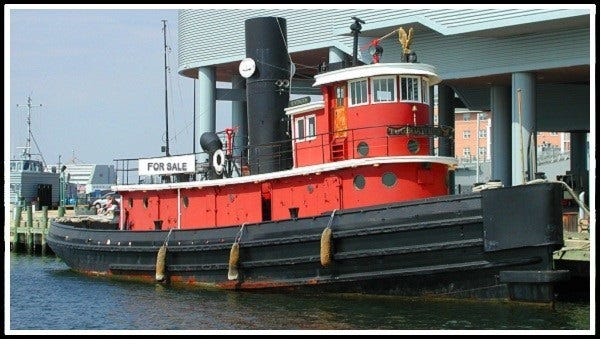

Sometimes, nostalgia or raw gut attraction for a particular vessel or form or type leads one to spend more in labor, time, and dollars on a conversion, refit, or refurb than makes cold financial sense.

Not too long ago, I received a query from a potential client who wanted to talk about refitting a partially-built motor yacht he was considering buying. H…