The Bayesian Tragedy: Anything That Can Go Wrong Will Go Wrong

SHOULD A COPY OF MURPHY'S LAW BE POSTED ON THE WALL OF EVERY YACHT DESIGN AND PLANS-REVIEW OFFICE?

DM from a FYBBO reader:

“As a naval architect having designed all manner of vessels, and worked in plan approval at [a major classification society] , I can tell you that Murphy's Law is definitely not ever considered….”

This snippet arrived in my inbox as part of a longer message received after I published an article on vessel stability and down-flooding, as they potentially related to the recent tragic sinking of the yacht Bayesian.

In that article, I remarked that my experience over the years has been that many naval architects and engineers working in yacht design and plans-review offices tend, at times, to forget Murphy’s Law — as do most of us involved in yacht building — when large, expensive, and profitable projects are at stake, and when demanding, ultra-wealthy buyers and owners focus primarily on aesthetics and convenience.

To be honest, I am not sure whether the intent of that reader’s comment was to confirm my opinion or denigrate it. But that’s really of little matter because I’d already set about wondering how often we in the yachtbuilding industry wax overly optimistic about problem-specific solutions we craft that don’t perform in the real world as they do on the drawing board or sketch pad — solutions that lead straight to new problems which are worse than those we set out to solve, or solutions that simply enable us to hide from ourselves the fact it would be better simply to “go back to the drawing board”.

While I’ve been thinking about that, I’ve continued to read a several very good articles about a number of as-built design features of Bayesian which may have contributed to her sinking — some of which articles support my own early (some have said premature) speculations:

➡️[ Bayesian Stability Calculus Suggests… Only Seconds To Save Lives ]⬅️

As the initial information-void about the design and construction of Bayesian (nee Salute) has been filled in by, for example, publication of her original Stability Book, what were initially vague shadows of technical questions have gained, IMO, substantive reality — particularly the disclosure that the yacht’s threshold angle of heel for serious down-flooding was a surprisingly low 45-degrees. Not to mention confirmation that her AVS (angle of vanishing stability) was only 73-degrees with her ballasted centerboard up. And her light-load AVS board fully down was only 84-degrees (significantly lower than the 90-degrees considered by most offshore sailors to be rock bottom minimum).

My intent here is not to reiterate these facts ad nauseam, but instead to ask why the builder moved forward without improving the really low threshold angle for serious down-flooding. I do have some ideas about that, which I’ll lay out for you shortly. but for now, I just want to point out I am not alone in being perplexed about that and some other technical issues. For instance, following my piece talking about the very low down-flooding angle, I received a note from a long-time online correspondent and friend, Carol Vasseur Scanu.

Carol is a retired founding partner (with her husband Paolo Scanu) in Studio Scanu, of Viareggio, Italy, which firm carried out more that 400 projects to 149 metres LOA, both sail and power, new and refit, plus major consulting, on five continents. Here is what Carol, who is not only knowledgeable, but outspoken, asked:

“I am curious, Phil, about the position of the vents. As you know, much smaller sailing boats and yachts do have vents that successfully avoid flooding. I don't see why a larger yacht, with a much greater height of the superstructure above the main deck, shouldn't be able to implement a safer venting program.

I will say one thing, when designing Georgia ,we were fortunate enough to have the LR [Lloyds Register] design approval office in Trieste. Italy. It is full of serious sailors, and they were quite cooperative in calculating things like the compression of the deck plating thickness around the 56+ metre mast.”

My reply to Carol was that when I was building tri-deck megayachts in the 40- to 50-metre range at Palmer Johnson some twenty years ago, we always sought to terminate engine room and other critical venting as high above the main weather deck as practical, without compromise to aesthetics. And it is hard to conceive of not doing the same in a tall-masted sailing yacht which will, at times, be heeling over under a press of sail (notwithstanding computer-driven sail control that factors in angle of heel on any given angle to the apparent wind). Granted, positioning exterior vent terminations up as high a possible might require some aesthetically inconvenient interior ducting, there should, nevertheless, be aesthetically acceptable options available that are well within the realm of functional possibility.

It’s pretty clear from the available documents that such questions came up, witness there do, in fact, appear to have been means provided for closing the engine room and HVAC vents against down-flooding. And the yacht was designed with watertight bulkheads fitted with internal WT sliding doors to maintain WT compartmentalization in five discrete units, any two of which could have (in theory) flooded, without sinking the vessel. In this context, a proviso contained in the original Stability Book is notable:

“AT SEA — Internal sliding watertight doors… may be left open, but consideration should be given to closing then when risk of hull damage and flooding increase (e.g. in fog, in shallow rocky waters, in congested shipping lanes, when entering and leaving port and at any other time the master considers appropriate. Sliding WT doors should be checked daily to ensure that nothing has been placed in way or where it might fall into the opening and prevent the door from closing. Internal hinged water tight doors…should remain closed but may be opened when passing through.”

➡️[ The Bayesian’s Stability Booklet — The Official Document ]⬅️

Aha! — There, you have it. It isn’t that potential problems were overlooked or even minimized. Apparently, quite the opposite. A number of potential serious problems were identified, and relatively complex solutions constructed to address those concerns, including the formulation of an elaborate operational protocol directed to the “Master” in a special note.

What apparently did not take place, however, was a final review or any action in light of Murphy’s Law.

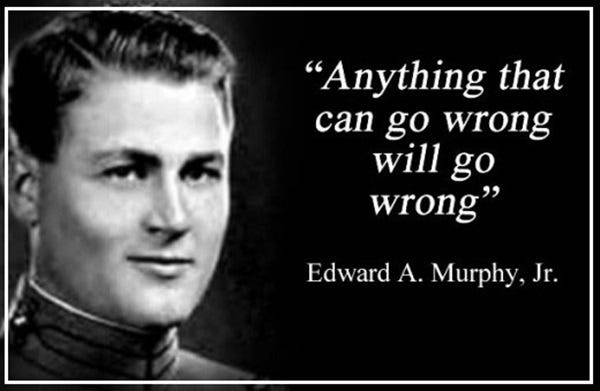

It’s always seemed to me that level of risk is the product of two separate factors: 1) the likelihood of a given mishap occurring, and 2) the severity of the consequences should that mishap, in fact, transpire. The first of these almost universally affects design decisions, but the second, although equally important, generally receives less consideration during the design spiral, especially when the first factor is perceived to be very low. If nothing else, when the risk is high, Murphy’s Law serves as a reminder that if you’re going to bet on the probabilities, you should nevertheless prepare for the improbable to happen. Because, as Edward A. Murphy Jr. was wont to say,

“Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.”

— Phil Friedman

Copyright © 2024 by Phil Friedman — All Rights Reserved

Afterword: I expect that when this article appears, I’ll receive some critical comments and even a few DMs questioning the propriety of discussing these matters “before all the facts have been determined and a proper report issues by authorities such as MAIB.” But before you pepper me with those comments and messages, please understand I believe firmly that position to be seriously wrong-headed — for at least two reasons:

1) The speculation(s) detailed here and in my previous two articles on the topic are based on facts already in the public domain. And by the way, the same can be said of the articles by other authors to which I’ve referred in this and my previous two pieces.

2) Beyond that, at least one private message received by me to date was from someone who claimed to be a friend of Captain James Cutfield, the master of Bayesian at the time of her sinking. That message said the writer found the speculative conversation and the social media rush-to-judgement of Captain Cutfield “sickening”. Well, for the record, note I haven’t said anything about Captain Cutfield or any member of his crew. As a matter of fact, from the available descriptions of their actions following the knockdown and during the scant few minutes they had before the Bayesian went down, it appears they conducted themselves with courage and professionalism.

My concern is several establishment pillars in the superyacht sector appear to be mustering to hang Captain Cutfield and one or more members of his crew out to dry — witness the widely circulated statements of Perini Navi’s CEO, which blame the captain and crew for an alleged series of errors and list of incompetence’s, not to mention the actions and statement(s) of the Italian Prosecutor. In light of that, I suggest it is actually in the best interests of the captain and crew of Bayesian for there to be a robust public discussion of potential/latent technical misjudgements in the yacht’s design and construction — because just such a public discussion before the completion of the investigation and the release of the “official” report will work to keep the “official” proceedings out fully in the sunshine.

Fair winds and safe harbors. — PLF